KATULAMPA RAFTING SENTUL BOGOR

Open trip untuk keluarga dan rombongan di hari Sabtu dan Minggu

Kabar gembira untuk Anda dan Keluarga di hari libur yang ingin berwisata memacu adrenalin di kawasan Sentul Bogor dengan ber rafting ria di Sungai Kali Baru,selesai rafting Anda dan Keluarga dapat melanjutkan berwisata di seputaran Sungai Kali Baru seperti mengunjungi SKI,Tas Tajur atau Agro wisata di Sentul Fresh yang dapat ditempuh hanya sekitar 20 menit dari lokasi Rafting,bisa Juga berkunjung Ke Jungle Land Sentul sekitar 25 Menit dijamin bebas Macet untuk menuju ke lokasi wisata tersebut dan..so pasti dengan biaya yang sangat terjangkau.

Biaya Paket Rafting Keluarga

Rp. 250.000/ Orang Berlaku untuk Hari Sabtu dan Minggu Minimal 5 Orang

biaya sudah termasuk :

- Tiket Rafting Durasi +2 Jam Jarak Tempuh 8 Km

- Equipment (Helmet dan Pelampung)

- Insurance

- Coffe break 1x (Kelapa Muda di sajikan utuh)

Bonus 1 x Lunch Box Jika Peserta Lebih dari 20 Orang

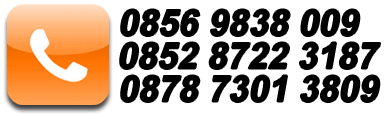

Pendaftaran Peserta Bisa Menghubungi di Nomor

0856 9838 009 /WA 0852 8722 3187

Pin BBM 5BB4FTEA

Kenapa harus di Rafting Katulampa Sentul?

- Dekat dengan Jakarta dan Kota Kota disekitarnya

- Jalur Bebas macet,jarak tempuh singkat

- Sungai nya masih Jernih(Jika tidak turun hujan)

- Memilik jeram yang bervariatif (Dam dan bebatuan)

- Lingkungan asri

- Debit air bisa di kontrol (Hulu di Bendungan Katulampa)

- Bebas banjir bandang

- Tiket murah

- Kru berpengalaman dan terlatih

- Dekat ke destinasi wisata lain di Kota Bogor.

Apa yang perlu diperhatikan jika ber rafting

- Sehat Jasmani dan Rohani (sudah pasti ya...?)

- Patuhi instruksi dari kru operator rafting

- Usahakan sudah Sarapan

- Simpan/titipkan barang berharga Anda baik baik

- Bawa salin pakaian dan perlengkapan toiletris

- Jangan mengotori dan merusak lingkungan area rafting

Hotel,Villa dan Bungalow di Sentul

Jika Anda ingin melanjutkan wisata Anda sampai esok hari,tak perlu khawatir jika Anda ingin menginap dengan biaya yang sangat terjangkau Kami menyiapkan Hotel,Villa dan Bungalow yang bersih dan bagus dengan suasana asri,nyaman dan tenang.

Segera Hubungi Nomor telpon diatas untuk mendapatkan paket fullboard dengan potongan/diskon khusus paket fullboard bundling dengan rafting dan kegiatan outing lainnya.